Fragmented Frontier: The Single-Asset Trap and the "Zombie" Miner

Written by David Morency

August 29, 2025

Figure 1.

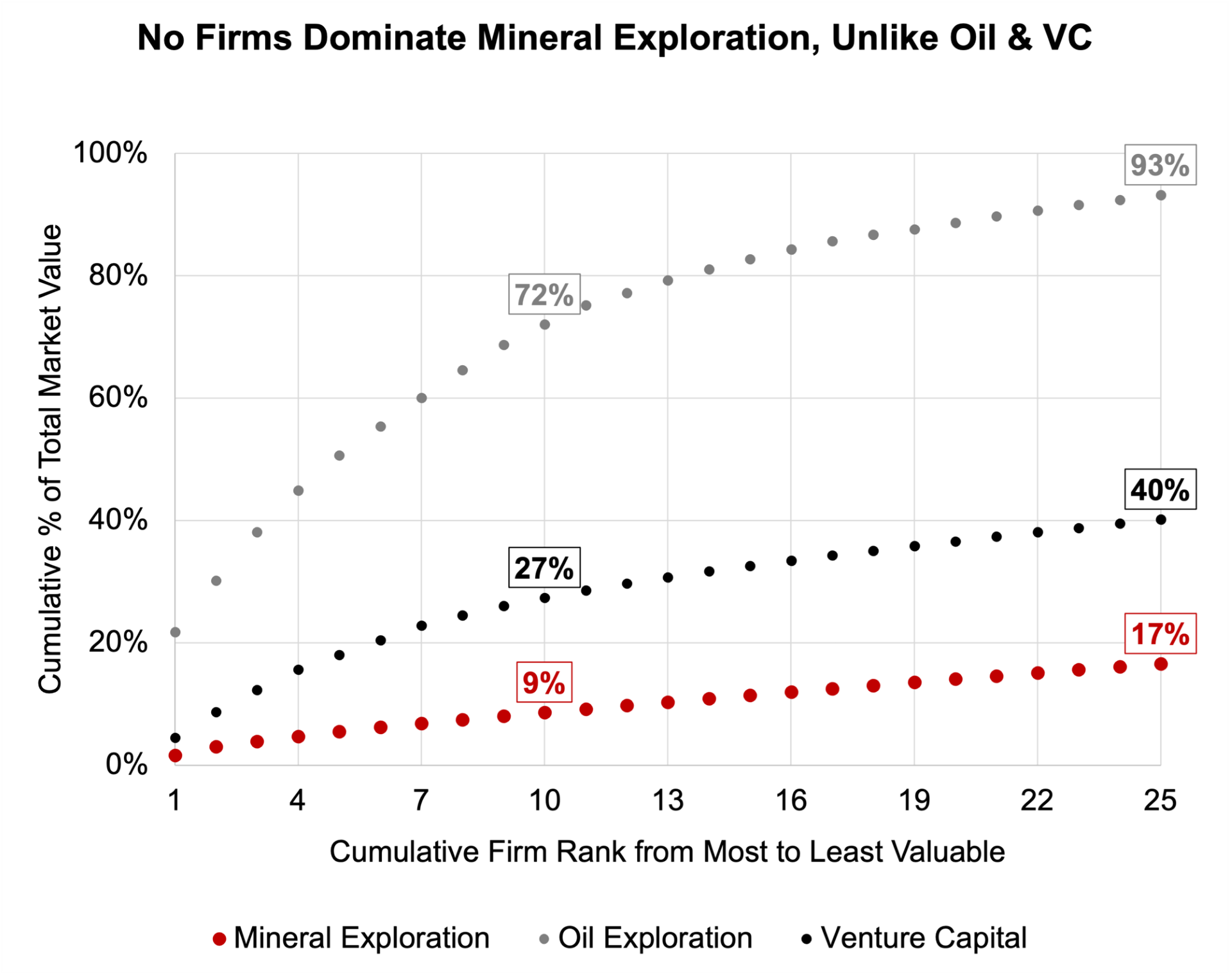

Compared to analogous industries, value within mineral exploration is highly fragmented.

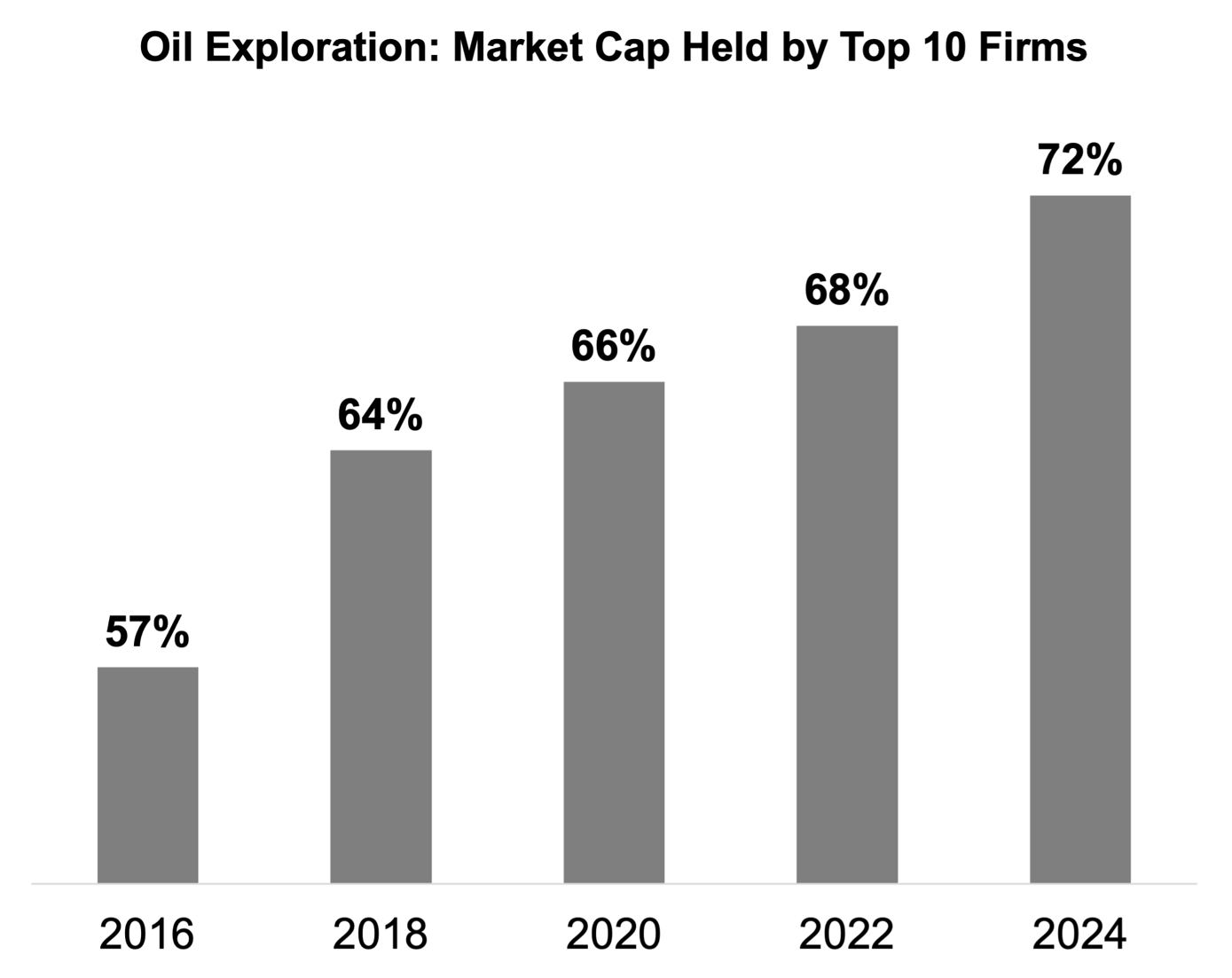

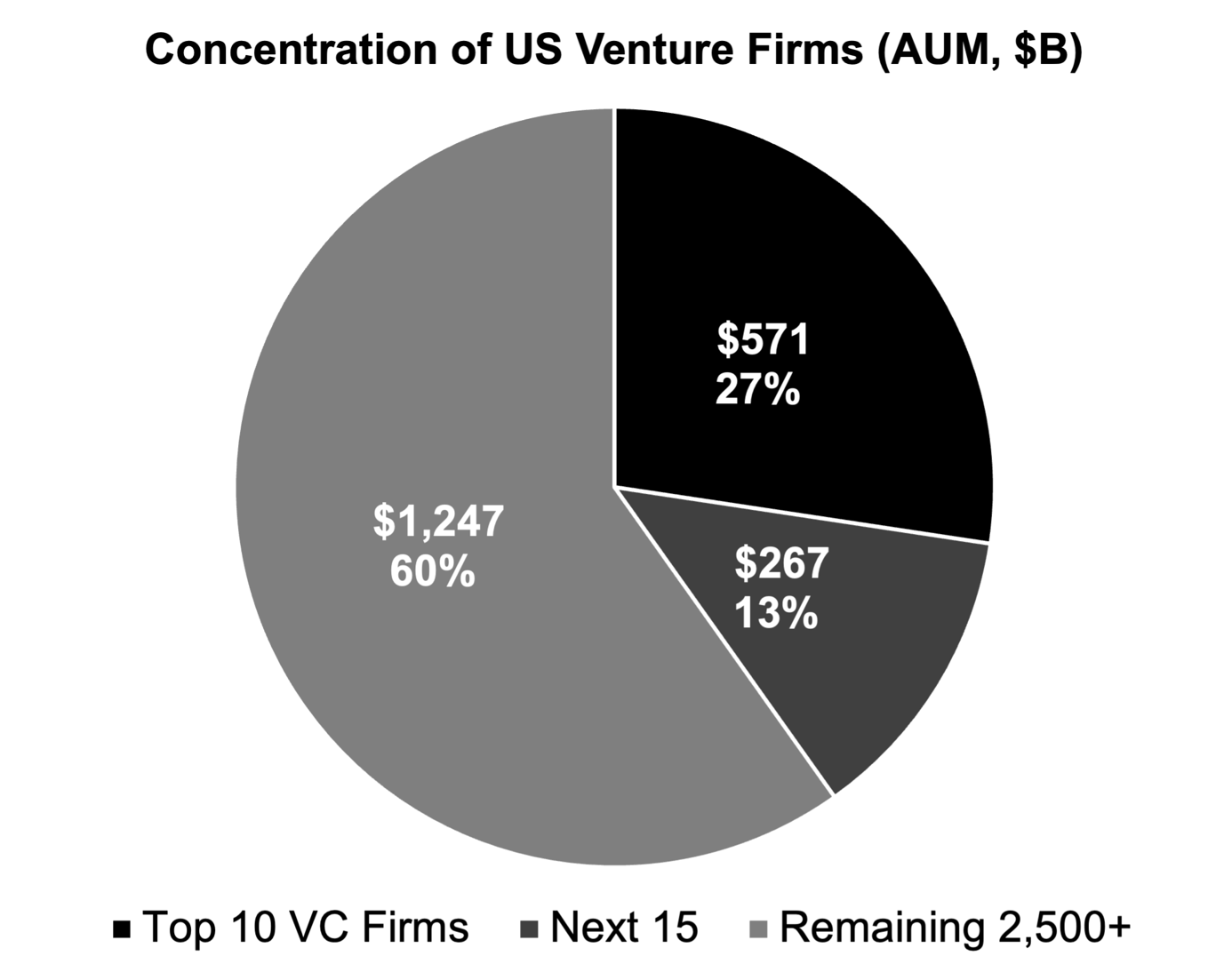

The top 10 junior explorers only capture 9% of their industry’s total market value, which pales in comparison to that of the top 10 VCs (27%) and oil exploration firms (72%).

This pattern persists further, as the top 25 junior explorers only capture a cumulative 17% of their industry’s total market value, versus 40% for the top 25 VCs and 93% for the top 25 oil exploration firms.

Figure 1.

Compared to analogous industries, value within mineral exploration is highly fragmented.

The top 10 junior explorers only capture 9% of their industry’s total market value, which pales in comparison to that of the top 10 VCs (27%) and oil exploration firms (72%).

This pattern persists further, as the top 25 junior explorers only capture a cumulative 17% of their industry’s total market value, versus 40% for the top 25 VCs and 93% for the top 25 oil exploration firms.

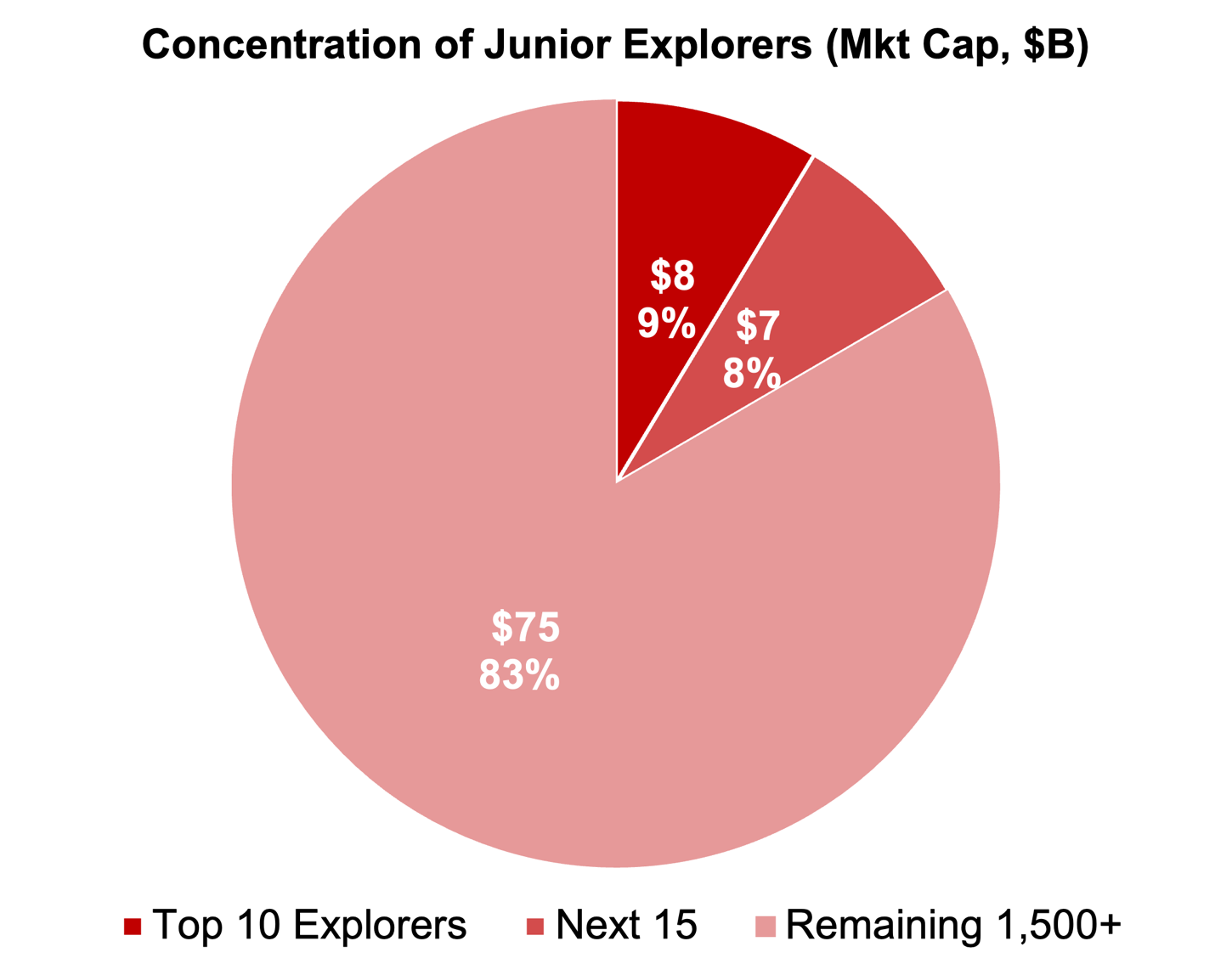

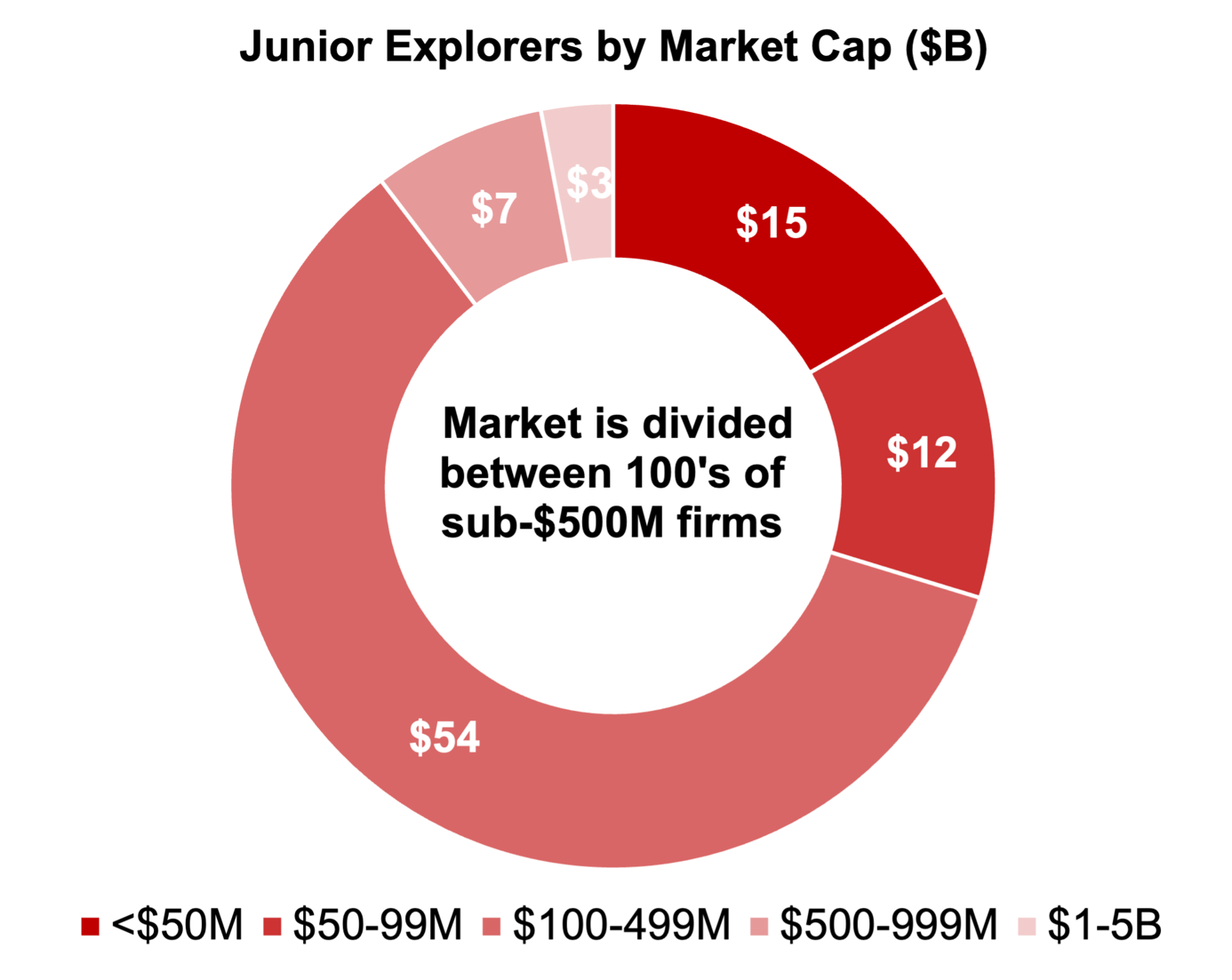

The junior mineral exploration sector is a paradox: it powers the mining industry’s R&D engine, yet remains hopelessly fragmented.

Thousands of undercapitalized players compete without a clear leader, in stark contrast to venture capital and oil exploration—industries that are 3–7x more concentrated. History suggests the sector is primed for consolidation and a breakout player [1].

The primary barrier to consolidation in mineral exploration is a chronic scarcity of capital, which creates a perverse incentive for survival. For a junior miner tied to a single asset, it is strategically untenable to abandon a project, even with poor results. The capital required to continue exploring is an order of magnitude less than that needed to acquire a new project. This dynamic compels management to double-down, perpetuating a cycle of dilutive financings for marginal programs and sustaining a legion of undercapitalized "zombie" mining companies [2].

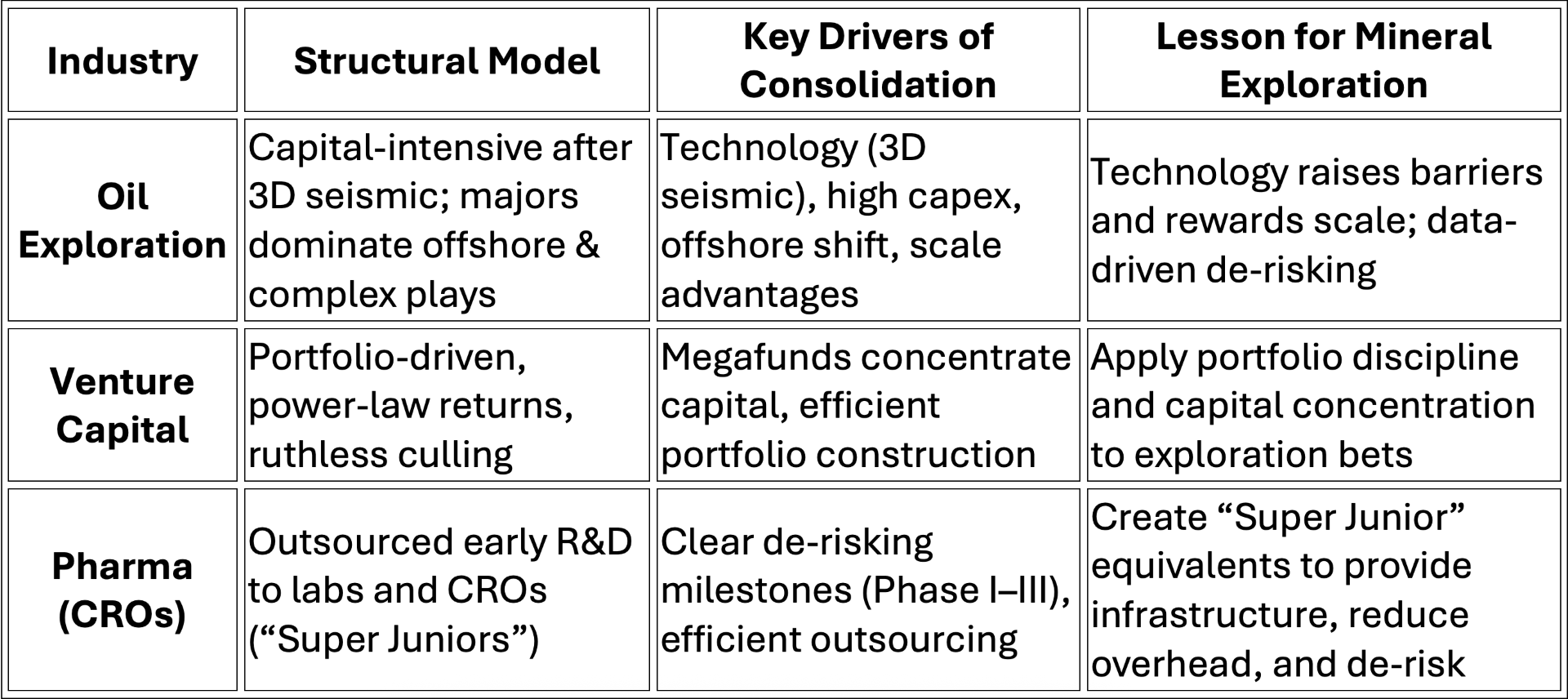

However, this broken model is not unique. By examining the precedents of analogous industries—such as oil exploration, venture capital, and pharmaceutical research—a clear playbook emerges for a technology-driven consolidator to capture a dominant share of the growing mineral exploration market.

Lessons from Other High-Risk Sectors

The structural flaws of junior mining become clear when contrasted with other industries that manage high-risk, capital-intensive projects. These sectors provide a roadmap for consolidation.

Oil Exploration: 3D Seismic Imaging

Seismic imaging transformed oil exploration by raising the scale and capital required to compete, accelerating consolidation in the sector. While 2D surveys in the 1960s and 1970s improved mapping, the true turning point came with 3D seismic in the 1980s and 1990s, which sharply increased discovery rates and reduced dry-hole risk [3]. Deploying these tools demanded major investments in acquisition equipment, computing power, and specialized talent—resources beyond the reach of many independents [4]. Exploration shifted from an entrepreneurial activity to one where well-capitalized firms held clear structural advantages.

This dynamic intensified as exploration expanded offshore, where billion-dollar seismic campaigns and complex data interpretation became essential. Smaller players, unable to sustain such commitments, increasingly sold prospects or were absorbed by larger firms, while seismic service providers themselves consolidated around a handful of global leaders like Schlumberger and CGG. By the 1990s, seismic had locked in a more capital-intensive model of exploration, cementing the dominance of majors across the most prospective basins.

The rise of U.S. shale briefly interrupted this trend in the early 2010s. Fracking relied more on securing acreage and repeating completion techniques, lowering barriers to entry and enabling thousands of independents to flourish. But by the late 2010s, volatility and investor pressure drove a fresh wave of bankruptcies and M&A, while seismic and data-driven exploration continued to reward scale outside of shale. By the mid-2020s, even the shale patch was consolidating rapidly, restoring the broader trajectory of concentration among large, well-capitalized firms [5].

Venture Capital: The Rise of “Megafunds”

Mineral exploration is analogous to venture capital, where high-risk ventures are best managed as a portfolio. The venture capital (VC) industry is built on a formal understanding of portfolio theory. VCs operate on the principle that returns follow a "power law" distribution: the vast majority of investments will fail, but a few outliers will produce exponential returns that cover all losses.

This dictates their entire model. A VC's primary function is disciplined portfolio construction, making many "shots on goal" to increase the chance of hitting an outlier [6]. This structure requires VCs to be unsentimental about failure. Companies that fail to gain traction are systematically cut off from follow-on capital, freeing up resources to focus on potential winners. The recent trend toward "megafunds" represents a powerful form of consolidation [7], concentrating immense capital on the most promising startups and starving competitors. For context, the top 10 VCs now control 27% of the industry’s value (proxied by AUM) [8] — standing in stark contrast to the fragmented mining exploration sector, where the top 10 firms only control 9% of the industry’s value.

Pharmaceutical Discovery: Outsourcing to “Super Juniors”

The pharmaceutical industry has created a highly efficient ecosystem for managing innovation risk by outsourcing the earliest, highest-risk stages of R&D to smaller biotech firms and specialized Contract Research Organizations (CROs). CROs act as end-to-end partners, providing the infrastructure and expertise—from trial design to data management and regulatory submissions—that small biotechs lack. Extending the analogy to mineral exploration, one could think of CROs as the equivalent of “Super Juniors,” with firms such as IQVIA and ICON capturing $15-30B+ valuations in the public markets.

The existence of CROs in this industry allows a small biotech project to be advanced through clear, regulated, de-risking milestones (e.g., Phase I, II, III trials). This specialized, outsourced model allows capital to be deployed with maximum efficiency toward de-risking the core asset.

The Inevitability of a New Model

The junior mining sector's single-asset trap, fueled by capital scarcity, is unsustainable. The lessons from more mature industries point toward a clear solution. A new model for mineral exploration must embrace a portfolio strategy to diversify risk and enable the disciplined culling of failed projects, as seen in the VC and oil and gas sectors. It must leverage technology to systematically de-risk assets before committing massive capital to drilling.

Drawing inspiration from the CRO model, a consolidator can act as a centralized hub of technical and capital markets expertise, providing efficient, specialized services to a portfolio of projects. This structure eliminates redundant overhead and allows for rational capital allocation. By creating a more resilient and de-risked investment vehicle, this new model will attract the stable, institutional capital needed to finally break the cycle of fragmentation and build the efficient discovery engine required for the 21st century.

Sources

[1] Based on Bloomberg data of publicly listed explorers listed on the TSX and ASX as of August 2025

[2] https://www.mining.com/web/zombie-miners-pulling-tsx-venture-exchange/

[3] https://mcee.ou.edu/aaspi/publications/2012/2_Chopra_et_al_2012.pdf

[4] https://library.seg.org/doi/10.1190/1.2112392

[5] Consolidation of oil exploration proxied by the Dow Jones Select Oil Exploration & Production Index

[7] https://news.crunchbase.com/venture/decade-megafunds-rise-insight-accel/

[8] Based on Pitchbook data as of August 2025